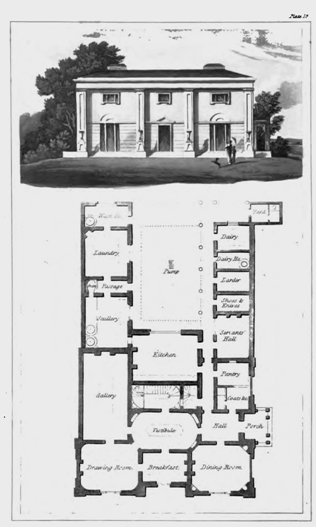

A VILLA. EXEMPLIFYING THE PROPER SITUATIONS FOR THE DOMESTIC OFFICES.

In forming this plan, care has been taken to avoid whatever experience has found objectionable relating to the domestic offices, and to afford facility of communication to the apartments, without subjecting them to inconvenience or offence. The pantry is near the dining-room, and commands the porch. The servants'-hall is beyond the door leading to the yard, and has the effect of being detached from the house, though really within it. The kitchen is arranged with the same advantages; the door opposite the pantry is only in use for the service of dinner. The scullery is wholly removed from the house. The laundry and wash-house are yet more retired, and immediately under the inspection of the housekeeper, who, in this arrangement, is considered as cook also. The knife and shoe-room adjoins the servants'-hall. The larder and dairy are farther removed from the inhabited parts; and the offices on this side are approachable by a trellis colonnade, so that at all seasons they are accessible with safety. The minor staircase leads to the chamber-landings and to the cellars; there is a stair to the cellar also, from the colonnade. The chambers contain three apartments for the men, three for the maid-servants, and a room for stores.

From the porch, a hall of small dimensions communicates with a waiting-room, which is a receptacle for coats, hats, sticks, &c. Water should be laid on to a wash-stand near the window; this room contains a water-closet. The dining-room entrance is from the hall, and is favourably situated for the service of dinner. The dining-room is unconnected with the retiring apartments; but a jib-door communicates with the vestibule, and precludes the necessity of passing through the hall to the drawing-room or gallery. The niches to contain candelabra at the sideboard end, and the corresponding recesses at the other angles, are suited to an architectural decoration consonant with the purposes of this room. The withdrawing-room, breakfast-room, and gallery or library, are approached from the vestibule, and from each other. The advantages of this arrangement are so obvious, that they are not treated of; but in the general adoption of the connected drawing-room and library, the mind becomes highly gratified on contemplating the acknowledged influence of female intellect, and those charms of social loveliness, that have allured the apartment of study from its obscure retreat.

The drawing-room is so formed as to avoid the dark shades which invariably collect in the corners of all rooms, and affords the means of a very elegant decoration. The gallery is lighted from the top, as its purpose is to contain pictures, marbles, bronzes, and books, and thus admit a beautiful variety of arrangements round it, forms the approach to the chambers.

|

|

|

The vestibule is always a most desirable appurtenance to a dwelling, and is here situated so as to afford additional ventilation; it reaches to the top of the building, and is surmounted by a lantern light; a gallery a gallery round it, forms the approach to the chambers. The vestibule opens to the staircase, and the staircase to this gallery. A water-closet is contained in the retired part of the staircase. The chambers above, are four, three with a dressing-room, and one without it.

Simplicity of character has been the leading object of this design. It will be seen that the extent of the house is aimed to be defined by pilasters, which are in number, four on the porch-front, four on the lawn-front, and two on the returning end; the remainder being plain walls, would be planted against, and hid by shrubberies, as there are no windows of the offices looking outwards.

The Palladian sashes of the dining-room, drawing-room, and the door of the breakfast-room, open to a stone terrace, which descends by two steps to the lawn. The terrace is so elegant in its character, and so useful as a promenade after wet weather, that it should be reluctantly, if ever, dispensed with.

|