In the autumn of 1853, Alfred and Emily Tennyson went house-hunting. Since their marriage in 1850 they had been searching for a home, but, as Emily's journal tells us, all suggestions and recommendations had been followed by disappointments. From March 1851 they lived at Chapel House in Twickenham, where their son, Hallam, was born in August 1852. In October of that year, Tennyson visited Bonchurch in the Isle of Wight. The poet's friend, Richard Monckton Milnes, had published a biography of John Keats in 1848 and it has been suggested that Tennyson's enthusiasm for Keats' poetry had led him to consider settling on the island where Keats had chosen to write. He was told that Farringford House, in the south of the island, near Freshwater, was available for rent from the Seymour family. Tennyson went to look at the house and found a substantial building in the neo-Gothic style fashionable at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It looked 'rather wretched with wet leaves trampled into the lawn' but he liked it enough to suggest that Emily should travel over and give him her opinion. Freshwater was very remote in the 1850s, and, having missed the steamer from Lymington, the Tennysons made the crossing in a rowing boat. Emily was immediately struck by the view from the drawing room window, and they decided that they would rent Farringford, furnished, with an option to purchase.

It looked 'rather wretched with wet leaves trampled into the lawn' but he liked it enough to suggest that Emily should travel over and give him her opinion. Freshwater was very remote in the 1850s, and, having missed the steamer from Lymington, the Tennysons made the crossing in a rowing boat. Emily was immediately struck by the view from the drawing room window, and they decided that they would rent Farringford, furnished, with an option to purchase.

A Poet of Landscape

Tennyson is a poet of landscape. Views and settings were of great importance to him. Born and brought up in the Lincolnshire wolds, he had found little inspiration in any of the places (Epping Forest, Cheltenham, Mornington Crescent) where he had lived after his family's move south from Lincolnshire in 1837. A compulsive walker, he could now climb daily onto High Down (later given the name Tennyson Down), sometimes pulling Emily with him in a small carriage. Surrounded by trees, Farringford had a sizeable estate, reaching down to the sea. Behind the house was a patch of tangled woodland known as the wilderness through which Tennyson opened up the old paths.  Close by, he built himself a summerhouse where he did much of his writing. The Pre-Raphaelite painter, William Holman Hunt, visiting Farringford in 1858, was delighted by the murals which Tennyson had been painting onto the panes of glass: 'writhing monsters of different sizes and shapes, swirling about as in the deep'. The summerhouse no longer survives, but visitors to Farringford tell of dragons, sea-serpents and kingfishers, appropriate subjects for a poet working on a cycle of Arthurian poems, The Idylls of the King. In another artistic venture, he made carvings of ivy-leaves in apple-tree wood, and terracotta casts from these were placed round the doors of farm cottages on the estate.

Close by, he built himself a summerhouse where he did much of his writing. The Pre-Raphaelite painter, William Holman Hunt, visiting Farringford in 1858, was delighted by the murals which Tennyson had been painting onto the panes of glass: 'writhing monsters of different sizes and shapes, swirling about as in the deep'. The summerhouse no longer survives, but visitors to Farringford tell of dragons, sea-serpents and kingfishers, appropriate subjects for a poet working on a cycle of Arthurian poems, The Idylls of the King. In another artistic venture, he made carvings of ivy-leaves in apple-tree wood, and terracotta casts from these were placed round the doors of farm cottages on the estate.

Keen Gardeners

From the start the Tennysons were keen gardeners, with Alfred cutting the grass and rolling the lawns. He would not hear of cutting down the trees which guaranteed his seclusion, even though this would have let through more light for his plants. He was to be seen digging and organising flower and vegetable beds in his gardens. 'I hope no one will pluck my wild Irises which I have planted', he wrote, 'if they want flowers there is the kitchen garden - nor break my new laurels etc. whose growth I have watched … I don't quite like children croquetting on that lawn. I have a personal interest in every leaf about it'. Some idea of the garden beds, full of flowers, can be seen in the paintings of Helen Allingham (fig. 4 and cat. 9), who illustrated The Homes and Haunts of Tennyson in 1905, after the poet's death.

Tennyson's garden was, as he put it himself, 'careless ordered'. This was an old-fashioned plan rather than the formal style coming into fashion in the 1850s. The natural scheme, with its apparently random shrubs and perennial plants was more like the gardens of today than the set and almost mathematical flower beds of the High Victorian period. At Farringford, as we can tell from Helen Allingham's paintings, flowers were to be found in profusion in the herbaceous borders of the walled garden.

Tennyson's poetry and Emily's journal tell us of their delight in the plants, birds, animals and insects around them. Friends and family related a number of passages from Tennyson's poems to particular aspects of Farringford life. Among them are the references to the cedar tree (cat. 7) and to the white-flowered yucca plant in 'To Ulysses', a poem addressed to a friend, Gifford Palgrave. Tennyson writes of seeing

My cedar green, and there

My giant ilex keeping leaf

When frost is keen and days are brief

- Or marvel how in English air

My yucca, which no winter quells

Although the months have scarce begun,

Has pushed toward our faintest sun

A spike of half-accomplished bells.

In 'The Flower' Tennyson writes of the love in idleness, or heartsease, grown from a seed which he had planted himself. It becomes a symbol for ideas (or his own poetry) which people at first dislike and then steal, copy and devalue.

Once in a golden hour

I cast to earth a seed.

Up there came a flower,

The people said, a weed.

To and fro they went

Through my garden-bower,

And muttering discontent

Cursed me and my flower.

The flowering yew trees, with the pollen blowing around them like smoke, found their way into two of Tennyson's poems. His son, Hallam, quotes his mother's journal for April 1868: 'There has been a great deal of smoke in the yew-trees this year. One day there was such a cloud that it seemed to be a fire in the shrubbery'. Hallam then notes that this was the inspiration for a passage from The Holy Grail, part of the Arthurian cycle. The old monk, Ambrosius, tells Sir Percivale that he has lived in the abbey for fifty years:

'O brother, I have seen this yew-tree smoke,

Spring after spring, for half a hundred years'.

Happy Days

The Tennyson memorial in Freshwater Church states that he passed his happiest days at Farringford. One indication of this was his insertion of a new poem in In Memoriam. This sequence of poems, making up an elegy for Tennyson's Cambridge friend, Arthur Hallam, was written over many years and finally published in 1850. Its popularity had a part to play in Tennyson's elevation to the position of Poet Laureate in the same year.

In poem II of In Memoriam, Tennyson writes of the yew tree, so often found in graveyards, as a symbol of enduring grief. When others trees are flowering in the spring, the yew does not experience a

'glow' or 'a bloom',

Who changest not in any gale,

Nor branding summer suns avail

To touch thy thousand years of gloom.

The experience of Farringford led Tennyson to write a balancing poem which suggests the coming of hope, of relief from the worst effects of sadness. Incorporated into the sequence as number XXXIX, this was written on 1 April 1868 and published in 1869. Tennyson tells us that the yew can also flower,

with its 'fruitful cloud and living smoke':

To thee too comes the golden hour

When flower is feeling after flower.

Inside the house at Farringford, Tennyson first chose an attic room for his study, but later moved down to the ground floor. A platform was built on the roof so that he could watch the stars. One of the most remarkable sights he witnessed was the passage of a comet in 1858. For a better view of this, Tennyson climbed up onto the down. On the night of the birth of their second son, 16 March 1854, Tennyson saw Mars in the constellation of the Lion. Lionel had been one of the names considered, and the baby was duly given that name.

Tennyson Poems

Among the poems written at Farringford was Maud. The extended monologue of a deeply disturbed man, it expresses Tennyson's anger at the Mammonism of the age. The speaker begins with the suicide of his father, who had suffered a financial disaster. He then tells of his love for Maud, the daughter of a neighbour who, he believes, has profited from his own father's fall. There is considerable evidence that the poem refers to a thwarted early relationship between the poet and Rosa Baring, a member of a wealthy family living at Harrington Hall in Lincolnshire. Certain features can, however, be related to the Isle of Wight, including the account of the crashing of the waves onto the shore. Having glimpsed Maud, the speaker stands in his 'own dark garden ground' and hears the sound of the sea:

Listening now to the tide in its broad-flung shipwrecking roar,

Now to the scream of a maddened beach dragged down by the wave.

Reviewers complained that these lines were exaggerated, but the scientist John Tyndall confirmed that this effect was not uncommon:

The pebbles and shingles on the beach are mainly flint, and emit a sharp sound on collision with each other. As the billows break and roll up the beach they carry the shingle along with them, and on their retreat they drag it downwards. Here the collisions of the flint pebbles are innumerable. They blend together in a continuous sound which could not be better described than by the line in 'Maud'.

More recently, Richard Hutchings, standing near the site of Tennyson's summer house 'heard the scream of the shingle at Freshwater Bay as it is dragged down by the waves'.

Maud was not much liked by the critics, but the profits from the volume enabled Tennyson to take up his option to buy the Farringford estate in 1856.Always nervous about money, Tennyson told his brother-in-law: 'We are going to buy this house and little estate here, only I rather shake under the fear of being ruined'.

Once they owned Farringford the Tennysons were able to move in their own furniture and to decorate and re-arrange the interior as they wished. One major change came in 1871 when they built a large room for parties and dances with a library above it. The walls of the house slowly filled up with paintings, sculptures and photographs, among them some from the collection of Italian and Flemish old masters amassed by the poet's father.

Maud ends with the speaker joining up to fight in the Crimean War. The Tennysons had heard the sound of cannon practice from across the Solent before the war began, and they learnt of the progress of hostilities from the newspapers. The famous military disaster, the Charge of the Light Brigade, took place on 25 October 1854, and was reported in The Times on 3 November. William Howard Russell told the full story there on 13 November and this was followed by other eye-witness accounts. On 5 December, on High Down, Tennyson drafted what has become his best-known work: 'in a few minutes, after reading the description in the Times'. The poem was revised over the next two days and then published on 9 December.

Another popular poem written in the summerhouse was 'Enoch Arden' . This is a poem of the sea, telling of a seafarer who tries to set up in business for himself, fails, and so undertakes a voyage on a shipwhich is wrecked. Enoch spends years on a desert island, is eventually rescued, and comes home to find his wife, Annie, remarried. He does not make himself known to her, and she only learns the truth of his return after his death. We know that the Pre-Raphaelite sculptor, Thomas Woolner, gave Tennyson the story for 'Enoch Arden'. Tennyson himself told a friend that the original events took place in Suffolk. The 'little port' of the poem could be in Tennyson's own Lincolnshire, but the landscape of the poem, with its 'Long lines of cliff', its 'chasm', its 'narrow cave' and its beach backed by 'a gray down' is not that of the North Sea coast. It is close to the views that Tennyson's would have seen walking in the area around Farringford. Tennyson would tell friends to 'listen to the sound of the sea' in the line 'The league-long roller thundering on the reef', where he describes the incoming tide on Enoch's island. He was capturing the effect of the waves as they crashed onto the coast of the Isle of Wight.

Farringford Visitors

There were many visitors to Farringford, among them Prince Albert who arrived in 1856, just as the Tennysons were preparing to decorate the house and move in their furniture. Charmed, he left with a bunch of cowslips, promising to bring Queen Victoria over from Osborne. Regrettably, this never happened, although the poet made several visits to her. One famous visitor who did arrive was Garibaldi, who came in 1864, and planted a Wellingtoniana, a hugely tall fir tree, near the house.

Tennyson writes of it as

the waving pine which here

The warrior of Caprera set,

A name that earth will not forget

Till earth has rolled her latest year -

Of the friends who visited Farringford from the mainland many stayed in the house while others established themselves at Plumbleys Hotel in Freshwater.  One of the earliest was the painter John Everett Millais, who helped the poet to sweep up the leaves and made a drawing of Emily and Hallam Tennyson for Tennyson's 'Dora'. This was among Millais' contributions to Edward Moxon's illustrated edition of Tennyson's Poems, published in 1857.

One of the earliest was the painter John Everett Millais, who helped the poet to sweep up the leaves and made a drawing of Emily and Hallam Tennyson for Tennyson's 'Dora'. This was among Millais' contributions to Edward Moxon's illustrated edition of Tennyson's Poems, published in 1857.

Two other guests invited to the Tennyson's home were the Reverend Frederic Denison Maurice and Mary Boyle. Both were sent poems and these tell us what Tennyson most valued about Farringford. Maurice, who was godfather to Tennyson's son, Hallam, was associated with the trends in the Church of England which were described as Broad Church. A liberal, he was one of the founders of the movement for social reform known as Christian Socialism. Shortly before Tennyson wrote the poem of invitation in January 1854, Maurice had fallen foul of the Council of King's College, London, for his belief that damnation need not be eternal. Tennyson drafted and then cut the lines:

Should half our churchmen bear a spite

To one so loving of the light

The bigot needs must bear a spite

To priests so faithful to the light.

Tennyson sets out to persuade Maurice to leave the 'noise and smoke of town' for Freshwater, where the poet watches the 'twilight falling brown'. Maurice could enjoy the garden and the delights of a civilised dinner table with 'honest talk and wholesome wine' and no 'scandal'. In a poem written much later, in 1889, Tennyson told Mary Boyle to 'change our dark Queen-city' and her 'realm of sound and smoke' for a clear sky, the call of the cuckoo and 'the elm tree's ruddy-hearted blossom-flake . . . fluttering down'.

Isle of Wight Friends

Local friends were of great importance in providing stimulation for the poet, who was easily bored and often restless. Fossil hunting was a popular pursuit at the time, and the scientist, Dr Robert Mann, and the rector of Brighstone, Mr Fox, were both happy to instruct him. Other friends began to buy or build houses near Farringford. On expeditions to London, Tennyson often stayed at Little Holland House in Kensington, home of Sara and Thoby Prinsep and a palace of 'high art'. Sara Prinsep was one of the talented and lively Pattle sisters, daughters of James Pattle, an Indian civil servant. The Tennysons knew another of the Pattle sisters, Julia Margaret Cameron, wife of Charles Hay Cameron. The Camerons first rented lodgings in Freshwater in 1857, and then, in 1860, bought two houses and knocked them together to form Dimbola. It was there that Julia Margaret learnt photography, and there are many stories of her pursuit of famous men in the exercise of her art, including, of course, her neighbour and his guests. The Camerons and the Tennysons, parents and children, were constantly visiting each other for more than a decade.

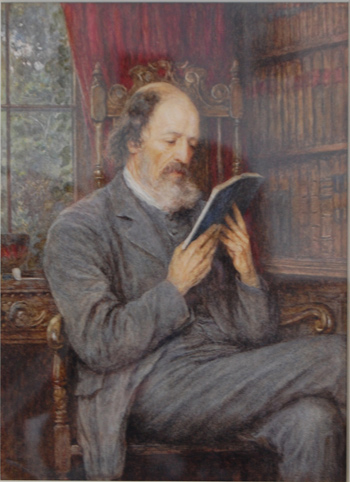

Through the Prinseps, Tennyson met the artist, George Frederic Watts, who first painted him in 1858 at Little Holland House, the painter's home for many years. Watts and Tennyson were good friends and, while a guest at Dimbola in 1862, Watts completed a portrait of Emily Tennyson . He then began on another of her husband. Work continued into 1863 on two, almost identical, heads, one, now in the National Portrait Gallery, the other exhibited here from a private collection these show Tennyson surrounded with laurel leaves, a distant glimpse of the white foam on the beach behind him. In 1864, the artist brought his teenage wife Ellen Terry to Farringford.

Through the Prinseps, Tennyson met the artist, George Frederic Watts, who first painted him in 1858 at Little Holland House, the painter's home for many years. Watts and Tennyson were good friends and, while a guest at Dimbola in 1862, Watts completed a portrait of Emily Tennyson . He then began on another of her husband. Work continued into 1863 on two, almost identical, heads, one, now in the National Portrait Gallery, the other exhibited here from a private collection these show Tennyson surrounded with laurel leaves, a distant glimpse of the white foam on the beach behind him. In 1864, the artist brought his teenage wife Ellen Terry to Farringford.

When the Prinseps were about to lose their home at Little Holland House, Watts commissioned the architect, Philip Webb, to build a house, The Briary, for them all in Freshwater. Watts and his second wife Mary were at The Briary in 1890 while Watts waspainting his last two portraits of Tennyson, Mary Watts writes of seeing her husband and his sitter walking towards the Briary. The poet's Russian wolfhound, Karenina , came first and then 'the poet, a note of black in the midst of vivid green, grand in the foldsof his ample cloak and his face looming grandly from the shadow of his giant hat'

The closest of Tennyson's Isle of Wight friends was Sir John Simeon, of Swainston Manor. The two men visited each other regularly, and Tennyson greatly enjoyed Simeon's conversation. More than a year after Simeon died in 1870 he began to write a fine elegy, recalling the day of his friend's funeral. Swainston was famous for its nightingales:

Nightingales sang in his woods:

The master was far away:

Nightingales warbled and sang

Of a passion that lasts but a day;

Still in the house in his coffin the

Prince of courtesy lay.

Crossing the Bar

The poem which Tennyson hoped would close all volumes of his poetry, 'Crossing the Bar' was written in October 1889 while he was crossing the Solent. He explained to his son the same evening that 'it came in a moment'. Tennyson's gift for natural observation is again apparent, as he tells how the full tide makes no noise and 'seems asleep', almost motionless.

But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.

The inspiration for 'Crossing the Bar' came as Tennyson returned to Farringford from his summer home at Aldworth, near Haslemere in Surrey. The increasing popularity of the Isle of Wight had resulted in intolerable incursions upon his personal privacy. A bridge was built so that he could reach the wilderness and the down without encountering his admirers in the lane, but some particularly insistent tourists, anxious to catch a glimpse of the great man, climbed trees or even walked into the garden.

A bridge was built so that he could reach the wilderness and the down without encountering his admirers in the lane, but some particularly insistent tourists, anxious to catch a glimpse of the great man, climbed trees or even walked into the garden.

From the late 1860s, the family left the island for the summer months, and it was at Aldworth on October 6 1892 that the poet died. A funeral close to Farringford was considered, but the decision was made to bury Tennyson in Westminster Abbey. However, Emily who died four years later, lies in the Freshwater graveyard. On 6 August 1897, a landmark memorial, a tall stone cross was unveiled on Beacon Down as a monument to the poet laureate.

LEONEE ORMOND

Professor Emerita of Victorian Studies at King's College, London

Author of: Alfred Tennyson: A Literary Life

> Would you like to holiday on Tennyson’s Isle of Wight estate? See our Self Catering Cottages