In 1853 Alfred Tennyson began searching for a new family home. On a visit to friends in Bonchurch, near Ventnor on the Isle of Wight, he was informed that Farringford was up for rent. His wife, Emily, wrote in her journal that “He went and found it looking rather wretched with wet leaves trampled into the lawn. However, we thought it worth while [sic] to go and look at it together”(October 1853). She goes on:

“We crossed in a rowing boat. It was a still November evening. One dark heron flew over the Solent backed by a daffodil sky.

We went to Lambert’s, then Plumley’s Hotel smaller than now. Next day we went to Farringford & looking from the drawing-room window, thought ‘I must have that view’ and I said so to him when alone. So accordingly we agreed with Mr. Seymour to take the place furnished for a time on trial with the option of purchasing.”

(Emily Tennyson’s Journal, November 1853)

The lease was for three years at £2 a week. Charles Tennyson writes that though the house was “relatively small” at this point, it “seemed a considerably larger place than [the Tennysons’] means justified”(‘Farringford, Home of Alfred Lord Tennyson’ by Charles Tennyson. Tennyson Society, 1976). Emily wrote of the couple’s arrival with their infant son on 25th November 1853:

“A great day for us. We reached Farringford. It was a misty morning & two of the servants on seeing it burst into tears saying they could never live in such a lonely place. We amused ourselves during the autumn and winter by sweeping up leaves for exercise and by making a muddy path thro’ the plantation into a Sandy one.”

(Emily Tennyson’s Journal, November 1853)

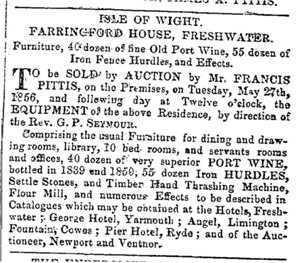

In 1856, George Turner Seymour finally sold Farringford to Tennyson, along with a sizeable estate called Priors Freshwater (see Priors Freshwater), for £4,350 – equivalent to just over £400,000 today. The sale documents still refer to the house as “Farringford Hill”. The process was infuriatingly protracted for Alfred, as Seymour wanted to remove all his furniture for auction before the Tennysons could install their own, and redecoration was also required.

[Hampshire Telegraph 1856 May 24; Issue 2955.]

(Hampshire Telegraph, 24 May 1856, Issue 2955)

The first problem the family encountered was the poor state of the drains, and by July 1856 Emily was describing them as “bad as they have never been before”(Journal, July 1856). Consequently, in November and December of that year, the first major work carried out by the Tennysons involved extensive work on the drains at Farringford.

In May 1859, bay windows – Emily Tennyson calls them “oriel windows” – were put in to the attic rooms, thus converting them from low-ceilinged, dark rooms into the much lighter, open rooms of today. In 1863, while Tennyson was travelling in Yorkshire, Emily supervised further alterations to the house; what these were exactly is unknown.

In 1864, during another of Tennyson’s absences, Emily set to work having “the back staircase altered and a grand arch made”(Journal, 27 June 1864). This may refer to one of the arches in the hall because in July she writes, “I am very glad that he likes the alterations I have made in the hall”(Journal, July 1864). It is relevant to note that the internal arches at Freshwater Court – a house built by well-known local builder Kennett, who also built the new library at Farringford in 1871 – are smaller versions of those at Farringford, suggesting that Kennett also constructed these. In 1868, during Alfred’s visit to Portugal, Emily again supervised the insertion of a small dormer window (still extant) into the west wall of Tennyson’s attic study. According to Tennyson’s friend William Allingham, the poet had wanted the window for sixteen years. It provides views in a westerly direction towards Moon’s Hill and the Downs above The Needles.

In 1871, it was decided to build a new study or library to contain Tennyson’s overflowing book collection. Like the main body of the house, it is built using a yellow brick in Flemish bond. To obtain a view to the north, large windows were inserted in the north wall, but to allow an uninterrupted vista a central section of the roof of the south servant’s wing opposite had to be cut away and a flat roof built instead. Although the original roof of the north wing was replaced by the present second storey, it too presumably would have required the same alteration. The library was heated by a large fireplace, still extant. At a later date, secondary double glazing was fitted and central heating arrived in the form of a pair of pipes that encircled the whole room at skirting board level.

GLOSSARY

dormer window: A window that projects vertically from a sloping roof.

Flemish bond: Brickwork in which ‘header’ bricks (bricks with their width exposed) are separated by one ‘stretcher’ brick (bricks with their long narrow side exposed), in an alternate pattern.

Based on the ‘Analytical Record’ of Farringford by Robert Martin: