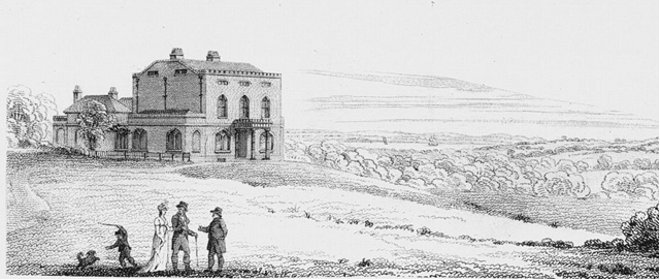

Farringford aroused little interest or comment in the guide books of the early 19th century, the one exception being William Cook’s A New Picture of the Isle of Wight (1808), which seemed more concerned with the views than the house itself:

“Farringford Hill: This elegant, newly-erected edifice, about half a mile from Freshwater Gate, is the residence of Mr Rushworth; as a situation certainly preferable to his more ancient mansion of Freshwater House, which, though spacious and convenient…yet may be thought to yield to the eligible situation of this new house. It is a tasteful structure of light brick, in the most cheerful of the Gothic style, placed on the declivity under the high down towards the Signal-house, and facing the whole extent of the island to the eastward. A more commanding situation could not well be chosen, and immediately contiguous is the beautiful display of the island of Freshwater, whose fertile and well-wooded lands appear as an extensive domain belonging to this house, and bounded by the river Yar.

It is finely sheltered from the prevailing south-west winds by the high down behind, and commands a view of the British Channel as well as the Solent Sea, separating the island from the Hampshire coast, which forms some very beautiful scenery from the house. The view of Freshwater Gate and Bay, with the whole range of coast to St Catherine’s, is particularly striking. And even from that distance, Farringford appears a conspicuous object. It is distant from Yarmouth about three miles.”

(A New Picture of the Isle of Wight by William Cooke. London, 1808)

The house was constructed from buff brick and comprised a central block with two parallel domestic wings adjoining on the west, creating a ‘U’ shape. A good idea of the original layout of the house may be ascertained from a sale advert for Farringford Hill that appeared in The Times, 7 January 1818. From the front door, a central hall stretched back to the main staircase at the rear of the hall passage. The drawing room was on the right of this front entrance, while the dining room was on its left. Both rooms were accessed from doors at the front of the hall. Behind these two rooms was located a library, which, judging by the dimensions listed, was where the Blue Room is today. This conforms very closely to a plan for a typical Georgian home presented by architect John Plaw in 1794 (see ‘Suggested plan for a house, illustrated in Rural Architecture’ in Regency Georgian Architecture). There were four bedrooms on the first floor, and four attic rooms.

The two wings to the rear of this central block contained the domestic areas, from where the servants worked. The north wing contained two stories, while the south wing was originally only a single ground floor storey. These two wings contained the kitchen, scullery, butler’s pantry, servant’s hall and laundry. From the servant’s hall, a staircase allowed access to four bedrooms for servants above. In Georgian buildings, the domestic rooms were either located in a basement or, in large country mansions, were situated on the ground floor below the first-floor piano nobile – the main living rooms of the family. However, in small and medium-sized houses and villas, it was advised servants’ rooms should be located at the back and built as low as possible so as not to hinder the views: “The Offices should be extended in a right Line from the building Northwards (proposing the Front a South Aspect) join’d only by a Corridore, and so low built, that the Vista's [sic] from the Chamber Windows might not be prevented being seen at the Ends of the House”(Lectures on Architecture by Robert Morris. London, 1734). The basement at Farringford contained the beer and wine cellars, a larder and a diary.

[The illustration appears in second edition of 1812 & 1813]

William Cooke’s engraving of Farringford Hill includes a small two-storey structure, incorporated into the south domestic wing. It is off-set from the building line of the south elevation of the domestic wing and occupies, coincidentally, almost the same position as Tennyson’s 1871 library extension. Part of it has been poorly drawn, as the line that represents the south east corner is missing and thus there is a confusing conflict of perspective. The stone stringcourse of the main house continues along the front of this structure. An arch of the blind arcade on the south elevation of the domestic wing can clearly be seen at the western end of the wing, and there is a similar blank arch in the structure itself. That these do not contain windows and are decorative, brick filled arches can be discerned by the artistic convention that Cooke has used for showing brickwork: the same broken line hatching used for brickwork has been used in the arches. Looking at a modern plan of Farringford, it will be noticed that there are two substantial cross walls in the south wing that correspond neatly with east and west walls of this strange structure. These cross walls can be explained as a thickening of the wall to allow the insertion of chimneys.

Although there are conflicting accounts about the location of the original drawing room, it is almost certain that this was located to the right of the original front door, and became the dining room in Tennyson’s time. An acquaintance of Sir Charles Tennyson – Tennyson’s grandson – wrote to him explaining this conclusion, having conducted extensive research into the history of the house:

“[This room] has far better decoration, both as regards the cornice, the fireplace and doors, than any other room on the ground floor. The room to the left of the front door was the dining room, since our ancestors always placed this room as far from the kitchen as possible, so as to avoid the smell of cooking. What is now the front hall [referred to as the ‘Blue Room’ as of 2017] would have been the study or work room where the Master of the House could interview his Retainers, and the room which is now the Bar [referred to as the ‘School Room’ as of 2017] would have been the Morning or Breakfast-room. Both the two front rooms had two windows, the drawing-room North and East through the alcove; the dining room, East and South. The East window through the present Drawing-room door & book shelves…has now, unfortunately, been blocked up.”

(Rev. Macdonald-Millar to Sir Charles Tennyson, 28 April 1955)

Rev. Macdonald-Millar’s conclusions are supported by the typical floor plan of a house this size, as laid out in John Plaw’s Rural Architecture. In addition, the room measurements of the original house confirm this.

At some point before 1819, the park around Farringford on its north and east side was created by engrossing a number of enclosures that had existed previous to it. These can be seen on an Ordnance Survey map of 1793. The new amalgamated ground was known as the “Lawn”.

Rushworth died in October 1817, and in 1819 his widow Catherine sold Farringford Hill and its grounds to Robert Gibbs of Thorley Farm. It was then purchased by Henry Shepherd Pearson of Lymington in 1821, who sold it to John Hambrough of Pipewell Hall, Northamptonshire (1798-1861), two years later.

GLOSSARY

blind arcade: An arcade that is composed of a series of arches that have no openings, instead being merely a decorative ornament on a surface wall.

stringcourse: A decorative horizontal band on the exterior wall of a building, usually formed of brick or stone. It features in Western architecture from the Roman to the modern age.

Based on the ‘Analytical Record’ of Farringford by Robert Martin: