This week I read some of the entries in The Farringford Journal of Emily Tennyson, 1853-1864 (1986) edited by Richard J. Hutchings and Brian Hinton. This book contains only some of Emily’s journals which she began when she married Alfred Tennyson in 1850. The only complete edition of her journals was edited by James O. Hoge and published in 1981. Unfortunately, my local library does not own a copy of Hoge’s edition so I’m not able to consult it.

Neither of these published editions contains the entries in Emily Tennyson’s original journals; when she helped Hallam prepare his father’s memoirs she recopied the entries she thought were important and destroyed the original journals. The copy she made while helping her son is held in the Tennyson archives in Lincoln.

It becomes clear on reading the journal that some entries cover several days. Also, when Emily refers to a he or him without having mentioned any men or boys, it is always a reference to her husband. She also uses the shorthand of calling him simply, ‘A.’.

What kinds of things did she write about?

Emily often recorded visitors to Farringford as well as visits she and/or Alfred made to others while they were living there. In these entries she mentions walks she or Alfred took with the visitors and presents they brought to the family. So, the journals offer a fairly comprehensive record of their social lives during these years.

Though they employed a gardener, Emily and Alfred seem to have undertaken quite a lot of the gardening work themselves. She repeatedly mentions Alfred rolling the grass or digging in the garden and she records what flowers they plant each year.

The journals also give us some insight into the family’s home life and the poet’s work because Emily seems to have made a record of each poem Alfred read aloud to her in the evenings. He read both works of his own and great works of literature such as plays by Shakespeare and poems by Milton.

When she mentions Tennyson’s readings of his own works, Emily’s response is always positive whether he was reading them while they were still in progress or rereading them to her years after publication. Each time a new edition of his poems came out she seems to have commented on the quality of the publication and on any illustrations included in it. In the coming months I’ll look at some of the editions of Tennyson’s work published in his lifetime and will draw on her responses to them in my blogs.

Christmas at Farringford

My primary reason for reading Emily’s journals this week was to find out how the Tennysons kept Christmas. Considering they both preferred being at home to being anywhere else, it is unsurprising that they spent Christmas at home between 1853 and 1864. The entries suggest that some of those Christmases were quiet family affairs, while others included visitors.

One constant, no matter how many people were at Farringford, is that they sought to entertain the children. For example in 1854 Emily wrote, ‘We keep Christmas by blowing bubbles for the children’ (page 18). Bubbles make another appearance in 1858 when poor weather threatens to ruin Christmas: ‘The Gentlemen blow bubbles for the boys the day being rainy’. I don’t think I’ve ever blown bubbles at Christmas, but it would have made a wonderful way to entertain two small boys when the weather made playing outside impossible.

Magic Lantern Shows

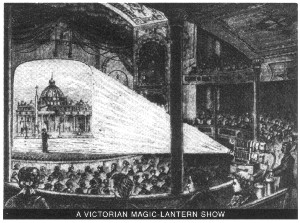

Another favourite Victorian entertainment makes an appearance in 1862 when Emily wrote, ‘The boys have the Magic Lantern’.

Magic Lantern shows involved projecting images onto a screen or blank wall for entertainment. We might find such shows tame in our world of computers, televisions, and cinemas, but in the mid-nineteenth century they would have been quite exciting. You can find examples of the kind of show Hallam and Lionel would have been treated to here.

Blindmans Bluff

The entertainment wasn’t all for the children, however. In 1855 Emily described a gathering of several friends and their relatives on Christmas Eve as follows:

The circle becomes formal & A. insists on a game of Blindman’s buff so we had a good child’s game of English Blindman’s buff which I for my part enjoyed. (page 29)

It is delightful to think of the poet laureate and his guests acting like children at Christmas!

Emily also mentions Christmas decorations. For example on Christmas in 1854 Hallam and Lionel ‘have pretty wreaths of laurel and holly on their heads’ (page 18). More spectacularly, she described the Christmas tree that a family friend ‘kindly prepared as a surprise’ for the family at Christmas 1859 and said that it ‘looks rather magical in the Antiroom when we open the drawing room doors’ (page 87).

How does your family celebrate the holidays? How do you bring light and light heartedness into the cold, dark days of December?