Often sharing in subject matter, Tennyson and the Pre-Raphaelites created a whole new series of characters so real that their images are familiar to us over 150 years later.

When we read these poems now, we associate the characters of the paintings so strongly with those of the poems, that it almost becomes impossible to separate each from the other. However, the reputation that Tennyson seems to have gained for writing weak or perhaps overly ‘Victorian’ women, is I think, due more to the impressions created by these paintings, than the strength of the characters within the poems, which have a personality often totally different to these images. Perhaps the most famous of these is John Evert Millais’ painting ‘Mariana’, painted around twenty years after the first publication of Tennyson's ‘Mariana’ poem.

‘All day within the dreamy house,

The doors upon their hinges creak'd;

The blue fly sung in the pane; the mouse

Behind the mouldering wainscot shriek'd,

Or from the crevice peer'd about.

Old faces glimmer'd thro' the doors

Old footsteps trod the upper floors,

Old voices called her from without.

She only said, "My life is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"’

[Main image: John Everett Millais, Mariana, 1851, oil paint on mahogany, Tate, London.]

The glowing colours of the picture are perhaps a little at odds with the ‘mouldering’ interior of the poem, portrayed in the painting only by a few leaves which have drifted to the floor of Mariana’s chamber. Similarly, the jewellike glowing colours of the painting are not ‘dreary’ at all, and the ‘blue’ of a fly would easily be lost in the brightness of this interior. Mariana’s curved, seductive pose, leaning away from the window, does not seem essentially symptomatic of despair. Her emotions, her loneliness, are forgotten in this painting, ‘Mariana’ is very much in the company of the viewer, and the deep pathos of the poem is removed.

[Edward Burne Jones, The Beguiling of Merlin, 1872-7, oil paint on canvas, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Liverpool.]

Burne Jones’ ‘The Beguiling of Merlin’ was painted between 1872 and 1877, where Tennyson’s ‘Idylls of the King’ were written between 1859 and 1885. Burne Jones frequently visited Tennyson during this period and it is not impossible to think that he read Tennyson’s ‘Merlin and Vivien’as Tennyson wrote it, or at least discussed the tale with him.

‘Then, in one moment, she put forth the charm

Of woven paces and of waving hands,

And in the hollow oak he lay as dead,

And lost to life and use and name and fame.

Then crying "I have made his glory mine,"

And shrieking out "O fool!" the harlot leapt

Adown the forest, and the thicket closed

Behind her, and the forest echoed "fool."’

Once again, however, the scene of the painting seems subtly at odds with that of the poem. Vivien, with her stolen spell book, and her side turned head, as well as her long dark clothing, looks less of the ‘harlot’ and more of the maiden, her expression is more sorrowful, than vitriolic, and the dead tree of the poem, in which Merlin is imprisoned is here in bloom. Vivien here is not the figure of terror and dread who alone has the power to vanquish Merlin, in this image, Merlin looks dissipated, weak and old – and Vivien’s triumph over him almost accidental.

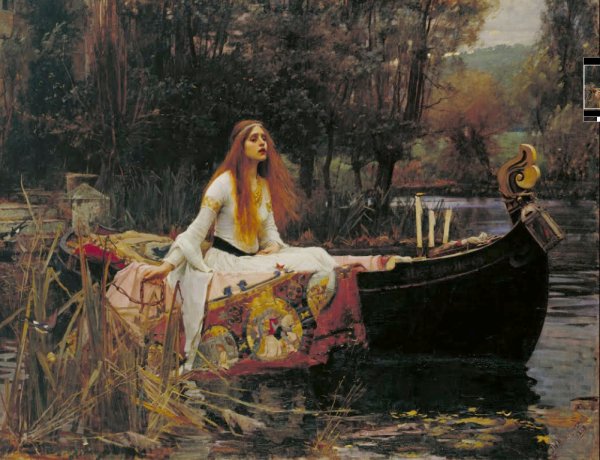

[John Everett Millais, The Lady of Shallot, 1888, oil paint on canvas, Tate, London.]

‘A cloudwhite crown of pearl she dight,

All raimented in snowy white

That loosely flew (her zone in sight

Clasp'd with one blinding diamond bright)

Her wide eyes fix'd on Camelot,

Though the squally east-wind keenly

Blew, with folded arms serenely

By the water stood the queenly

Lady of Shalott.

With a steady stony glance—

Like some bold seer in a trance,

Beholding all his own mischance,

Mute, with a glassy countenance—

She look'd down to Camelot.

It was the closing of the day:

She loos'd the chain, and down she lay;

The broad stream bore her far away,

The Lady of Shalott.

The figure in Waterhouse’s 1888 painting ‘The Lady of Shallot’, looks young and naïve and her expression tragic, this is the ‘stony’ eyed damsel of the poem who cares nothing for the ‘squally east-wind’ standing ‘queenly’ upon the shore.

‘A longdrawn carol, mournful, holy,

She chanted loudly, chanted lowly,

Till her eyes were darken'd wholly,

And her smooth face sharpen'd slowly,

Turn'd to tower'd Camelot:

For ere she reach'd upon the tide

The first house by the water-side,

Singing in her song she died,

The Lady of Shalott.

Under tower and balcony,

By garden wall and gallery,

A pale, pale corpse she floated by,

Deadcold, between the houses high,

Dead into tower'd Camelot.

Knight and burgher, lord and dame,

To the planked wharfage came:

Below the stern they read her name,

The Lady of Shalott.’

Waterhouse’s Lady is not in control of her own fate, she drifts upon the river, alternatively, Tennyson’s ‘Lady of Shallot’ knows what she is doing when she breaks the curse and sings her own death lament with a strength of will almost impossible to comprehend. A figure frequently presumed to be weak, but with an internal strength hidden within the words of the poem, the fate of the character ‘The Lady of Shallot’ has been determined, not by the poem, but instead, by the painting.