A feeling Allingham recorded of a visit to Farringford in June of 1865 reveals both one of the reasons he and Tennyson got along so well and why he failed to settle in London in his first two attempts (he would eventually succeed): both poets are deeply moved by and connected to nature.

After dinner on 25 June, Allingham records going ‘to the top of the house alone’ and having ’a strong sense of being in Tennyson’s; green summer, ruddy light in the sky’ (p 117). He equates Tennyson’s presence with the natural beauty of the summer sunset. Allingham’s accounts of visits to Farringford almost always include descriptions of walks he and Tennyson took and their responses to the natural beauty they see along the way.

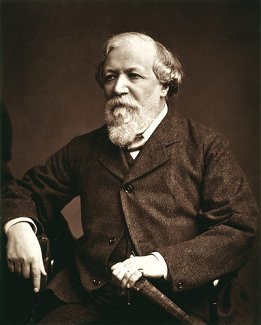

Tennyson, Allingham, and Browning

Allingham has quite a lot to report about Robert Browning in his Diary; there are several mentions of Browning early in the diary, and they grow in number after Allingham finally succeeds in settling in London in 1870 and the two poets become better friends.

Allingham has quite a lot to report about Robert Browning in his Diary; there are several mentions of Browning early in the diary, and they grow in number after Allingham finally succeeds in settling in London in 1870 and the two poets become better friends.

In the 1860s, however, when he discusses Browning, more often than not, Allingham is discussing his work rather than his personal relationship with the poet. When Tennyson and Allingham discuss Browning, Allingham gets the impression that Tennyson ‘has a very strong personal regard’ for him (p 127). Allingham reports that Tennyson said, ‘“Browning must think himself the greatest man living. I can’t understand how he should care for my poetry. His new poem has 15,000 lines—there’s copiousness! I can’t venture to put out a thing without care”’ (127-128).

Tennyson’s statements about Browning seem to complicate Allingham’s assessment of ‘strong personal regard’. Suggesting that Browning ‘think[s] himself the greatest man living’ is hardly complimentary, and is a long way from Tennyson saying that he thinks Browning is great. His comment about Browning’s ‘copiousness’ and his own inability to publish anything ‘without care’ are also implicitly critical. He seems to be acknowledging that Browning is capable of producing large quantities of poetry, without commenting on its quality. Still, Allingham’s understanding of the conversation is based on it in its entirety and we have only the reported phrases. Perhaps the main tenor of Tennyson’s comments was complimentary to Browning’s work.

Tennyson, Allingham, and Byron

It seems that whenever two poets meet, poetry is a frequent topic of conversation. As we have seen with their discussion of Browning, Allingham and Tennyson are no exception to this rule. In a later meeting, 18 May 1866, they turn to a discussion of the poetry of Byron, after discussing Browning’s comments to Allingham regarding Tennyson’s use of ‘white peacocks’ in ‘The Princess’ (Browning said, ‘”Tennyson’s taken to white peacocks! I always intended to use them”’, as though both poets couldn’t use them!) (p 131).

It seems that whenever two poets meet, poetry is a frequent topic of conversation. As we have seen with their discussion of Browning, Allingham and Tennyson are no exception to this rule. In a later meeting, 18 May 1866, they turn to a discussion of the poetry of Byron, after discussing Browning’s comments to Allingham regarding Tennyson’s use of ‘white peacocks’ in ‘The Princess’ (Browning said, ‘”Tennyson’s taken to white peacocks! I always intended to use them”’, as though both poets couldn’t use them!) (p 131).

Allingham reports that Tennyson ‘greatly admired [Byron] in boyhood, but does not now’ (p 132). The strength of his youthful passion for the Romantic poet is clear in Tennyson’s description of his response to his death: ‘”When I heard of his death […] I went out to the back of the house and cut on a wall with my knife, “Lord Byron is dead”’ (p 132). The youthful Tennyson needed to memorialise the dead poet for himself.

As the conversation continues, Tennyson reveals why his feelings changed; as he as matured as a poet, Tennyson’s criteria for judgement have changed. He says, ‘“Parts of Don Juan are good, but other parts badly done. I like some of his small things”’ (p 132). Allingham seems to agree and then goes on to discuss how vulgar some of Byron’s poetry is and suggests this is the reason for its popularity.

This prompts the following exchange:

T.—“Why am I popular? I don’t write vulgarly.”

A.—“I have often wondered that you are, and Browning wonders.”

T.—“I believe it’s because I’m Poet-Laureate. It’s something like being a lord.” (p 132)

It is remarkable how many of these conversations turn from the poet being discussed to discussions of Tennyson’s own poetic insecurities. It seems almost absurd that he, or anyone else, should wonder why he’s popular—to us it is almost too obvious to explain. We have the benefit of hindsight and know that Tennyson’s work will stand the test of time, so it is easy for us to forget that he couldn’t have our certainty.

Tennyson’s Unflappable Dignity

Through the remaining years at Farringford, Tennyson and Allingham’s visits continue along the lines I’ve already described. Only occasionally does Allingham give some new insight into the relationship and his feelings for the Great Man, as he called him in his account of their first meeting.

One of these insights appears in the account of a visit in November of 1866. He reports Tennyson’s readings of ‘a number of songs of his under the general title of The Window or, The Loves of the Wrens ’ which were set to music by Arthur Sullivan (p 146). Tennyson says of the Songs, ‘“They’re quite silly!”’ (p 146).

Allingham quotes the songs and comments on their kinship with nursery rhymes. He also describes Tennyson’s delivery: ‘In reading this, T. jumped round most comically, like a cock-pigeon. He is the only person I ever saw who can do the most ludicrous things without any loss of dignity’ (p 146). I’ll leave it with you to judge whether Tennyson’s inherent gravitas prevented his loss of dignity, or Allingham’s perception is clouded by his regard for the Great Man.

The Post-Farringford Years

Tennyson and Allingham maintained their friendship until Allingham’s death on 18 November 1889. They saw less of one another after Tennyson moved to Haslemere and Allingham moved to London (when he accepted first the sub-editorship of Fraser’s Magazine and then the editorship). Over the years the two men met up when they could, whether at Tennyson’s home or in London. Notably, after his marriage, Allingham and his wife Helen took lodgings near the Tennyson’s new home for several months and the poets saw at least as much of each other as during the ‘Farringford years’.

If you’re interested in Allingham and his relationships with the great writers and thinkers of the nineteenth century, I heartily encourage you to read his Diary in full. I, of course, have focused on Allingham’s relationship with Tennyson, but the diary contains much, much more. Allingham was friendly with, among many others, the Darwins, the Brownings, and Marian Evans Lewes (George Eliot) and her partner George Henry Lewes. His eye for detail and careful recording of events and conversations make Allingham’s Diary an interesting and entertaining read.